A guide to better embedded C++

Disclaimer: this, by no means, is not a definitive description of the whole embedded-specific development. This is just a small good practice about interaction with hardware.

Embedded is a wonderful versatile world which allows developers to create various interesting everyday devices (in collaboration with the hardware team).

The motivation behind this post is pretty simple: there is a lot (A LOT) of bad embedded code. There are several reasons for that:

- No background programming experience or education. Very often electronics students are taught plain C or C with classes (watch Kate talk about that).

- Difficult debugging. Most embedded systems are slow and have very limited debug abilities (sometimes even none of them at all). This is not a problem per se but may lead to numerous hotfixes and spaghetti code.

- Exotic architectures (where the byte is 24 and 32 bit long) with various compilers. Previously it used to be mostly custom stuff, but now processor manufacturers tend to fork some GCC or LLVM version and build a custom toolchain. This leads to problems with code reuse and significantly slows down the new standards adoption.

Long story short, the goal is to convert this code (CubeMX, STM32):

void SystemInit_ExtMemCtl(void)

{

__IO uint32_t tmp = 0x00;

register uint32_t tmpreg = 0, timeout = 0xFFFF;

register __IO uint32_t index;

RCC->AHB1ENR |= 0x000001F8;

tmp = READ_BIT(RCC->AHB1ENR, RCC_AHB1ENR_GPIOCEN);

GPIOD->AFR[0] = 0x00CCC0CC;

GPIOD->AFR[1] = 0xCCCCCCCC;

GPIOD->MODER = 0xAAAA0A8A;

GPIOD->OSPEEDR = 0xFFFF0FCF;

GPIOD->OTYPER = 0x00000000;

GPIOD->PUPDR = 0x00000000;

GPIOE->AFR[0] = 0xC00CC0CC;

GPIOE->AFR[1] = 0xCCCCCCCC;

GPIOE->MODER = 0xAAAA828A;

GPIOE->OSPEEDR = 0xFFFFC3CF;

GPIOE->OTYPER = 0x00000000;

GPIOE->PUPDR = 0x00000000;

// ...

/* Delay */

for (index = 0; index<1000; index++);

// ...

(void)(tmp);

}

To something like this:

void SystemInit_ExtMemCtl() {

rcc.Init();

gpio.Init();

}

Why is it even a problem?

The code in question is hard to read, understand and maintain. The worst is that it’s all true even for the developer who wrote it in the first place. Give him a break for a couple of months and he won’t remember what GPIOE->MODER is.

We can make this code better with the help of two bright thoughts from smart men:

All problems in computer science can be solved by another level of indirection

— David J. Wheeler

C++ is a zero-cost abstraction language

— Bjarne Stroustrup

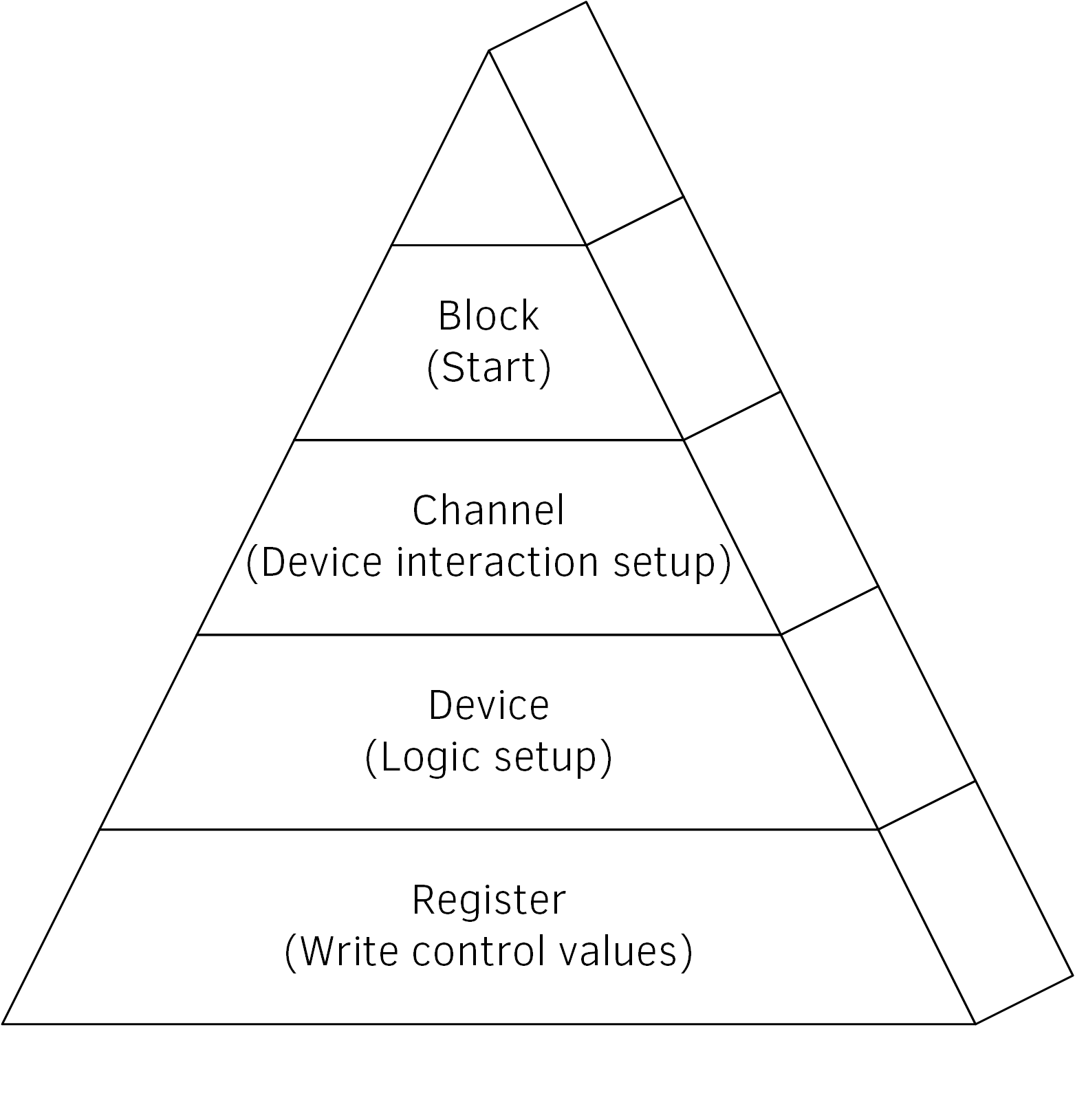

The idea behind this is the possibility to create abstractions and separate layers with no performance penalty. When all is said and done, the compiler will optimize out all of the high-level abstractions and generate exactly the same code. Most of the hardware device’s levels of indirection may be represented using the following drawing:

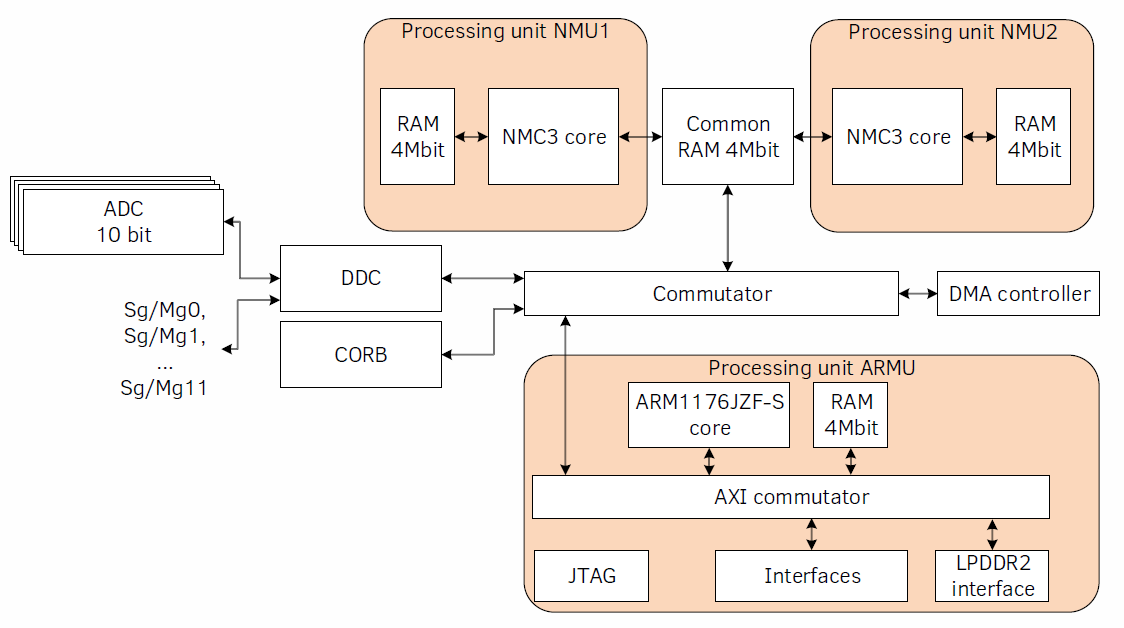

Imagine you have a board with some chip on it and your job is to set up some block. First of all, you open the datasheet and see something like this:

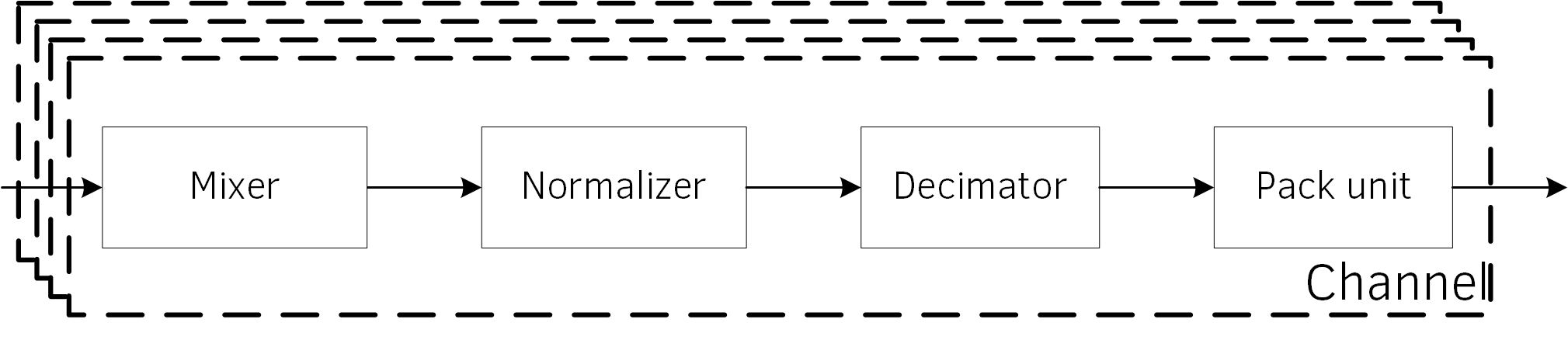

Ok, we have a vague understanding of the SoC. Our job is to make the DDC (digital down converter, very useful stuff often used in hardware-based digital signal processing) work as we want to. The simplified schematic is below:

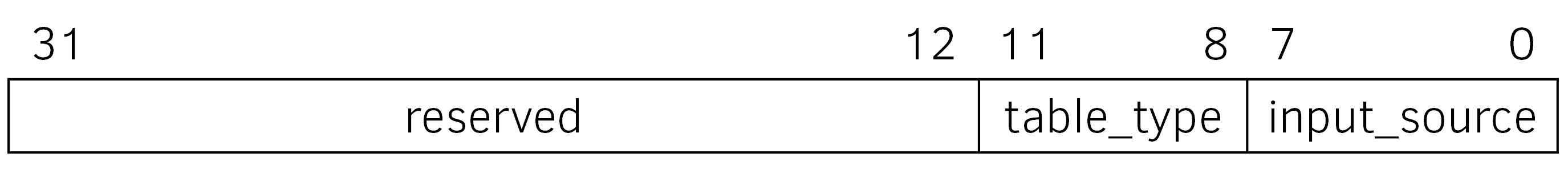

So let’s build our abstractions! According to the diagram above, we start from the very bottom, very low-level. We start with registers. Usually, they’re represented in documentation as something like this:

Numbers above mean bits, below are the fields, and this image is usually followed by the table with fields description. It is worth saying, that working with registers usually mean:

- A lot of work with bit-fields

- A possibility of a value change outside of the program flow

Unfortunately, a lot of embedded low-level libraries deal with registers this way:

*(volatile std::uint32_t*)reg_name = val;

It takes register address, stored at the reg_name variable (or even #define-constant), casts it to the volatile pointer, dereferences it and stores a value. This is bad for several reasons:

- The code is hard to read and maintain

- Virtually no possibility for encapsulation and raise an abstraction level

- When there are several registers functions usually turn into the code spreadsheet (more than that, it is usually copy-pasted)

There is, however, an alternative. The register in question may be represented as a structure:

struct DeviceSetup {

enum class TableType : std::uint32_t {

inphase = 0,

quadrature,

table

};

std::uint32_t input_source : 8;

TableType table_type : 4;

std::uint32_t reserved : 20;

};

If the internal fields require any recalculation, this may be done by implementing the GetFoo() and SetFoo() methods. By the way, I’m very excited about this proposal to allow default member initializers for bit-fields.

The next step is to place the object of this structure in the corresponding memory. Depends on what your codebase prefers, this may be done as placing a pointer, a reference, or using a placement new:

auto device_registers_ptr =

reinterpret_cast<DeviceSetup*>(DeviceControlAddress);

auto &device_registers_ref =

*reinterpret_cast<DeviceSetup*>(DeviceControlAddress);

auto device_registers_placement =

new (reinterpret_cast<DeviceSetup*>(DeviceControlAddress)) DeviceSetup;

But wait, earlier I said, that register values may change outside of the program scope! In current realization, a compiler is free to cache the object and you will be reading cached value, which is not what we’re expecting.

There is a way to tell the compiler that the value may change, and it’s volatile. I know that this keyword is being misused by a lot of programmers and it has a reputation like goto statement. But it was made for this type of situations (this is a great place to start).

volatile auto device_registers_ptr =

reinterpret_cast<DeviceSetup*>(DeviceControlAddress);

volatile auto &device_registers_ref =

*reinterpret_cast<DeviceSetup*>(DeviceControlAddress);

volatile auto device_registers_placement =

new (reinterpret_cast<DeviceSetup*>(DeviceControlAddress)) DeviceSetup;

Now, we’re certain, that every read will be performed.

N.B. Accessing registers modified by the hardware may be treated as a multi-threaded application. Therefore, it is worth considering using

std::atomic<T*>instead ofvolatile T*. Unfortunately, our production compilers don’t fully support C++11 (NM SDK is C++98 with no STL whatsoever, ARM Compiler 5 has C++11 at language-level, but their highly embedded-optimized STL is C++03), so I can’t battle test it. However, compiler explorer shows promising disassembly: link.

Ok, the register part is over, adding a level of indirection: let’s set up a device. Most of the time, devices can be represented as a group of registers or other devices, as simple as that:

struct Mixer {

NCO nco;

MixerInput mixer_input;

// ...

};

Developers should implement common setup methods, as well as access methods for a fine-tuning:

NCO& GetNCO() {

return nco;

}

Going further up the abstraction pyramid we create a channel, consisting of devices:

struct Channel{

Mixer mixer;

Normalizer normalizer;

Downsampler downsampler;

PackUnit pack_unit;

};

And, finally, the whole DDC as an array of channels and some control registers:

struct DDC {

std::array<Channel, number_of_channels> channels;

struct ControlRegisters {

// ...

} control_registers;

};

This whole thing is called hardware abstraction layer (HAL). It provides the programmatic interface for the developer to interact with the hardware. The greatest thing about HAL is that you can substitute real hardware with the PC-model. This is a big deal to talk about in another article. Shortly, the advantages of models are:

- Models allow developers to write programs without the actual hardware. This situation occurs during the development of the processor or the board.

- Model development enhances the understanding of the hardware developers are working with.

- With models, you can debug in post-mortem mode. Collect command dump or some information and run your model with that data.

In this article, I tried to convince you that the hardware-oriented code can be written in a good way and with no pain for future maintainers.