CPU instruction set dispatcher

- Introduction

- Benchmarking first

- Creating a library

- Delayed library loading

- Generating multiple libraries

- Detecting the processor architecture at runtime

- Using the library

TL;DR: In this blog post we’ll generate multiple libraries from the same source code with the various architecture flags. Later on, at the runtime, an application selects the most appropriate library based on the instruction set and will gain a 3x performance gain on the simple function I’ve decided to implement.

Introduction

Modern processors are often much more capable than we think because the CPU vendors care about us, fellow programmers. There’s an amazing talk by Matt Godbolt, go check it out if you haven’t already. The popcnt example blows my mind to this day. Briefly: modern (Haswell and forth) processors have a special instruction which counts the number of set bits.

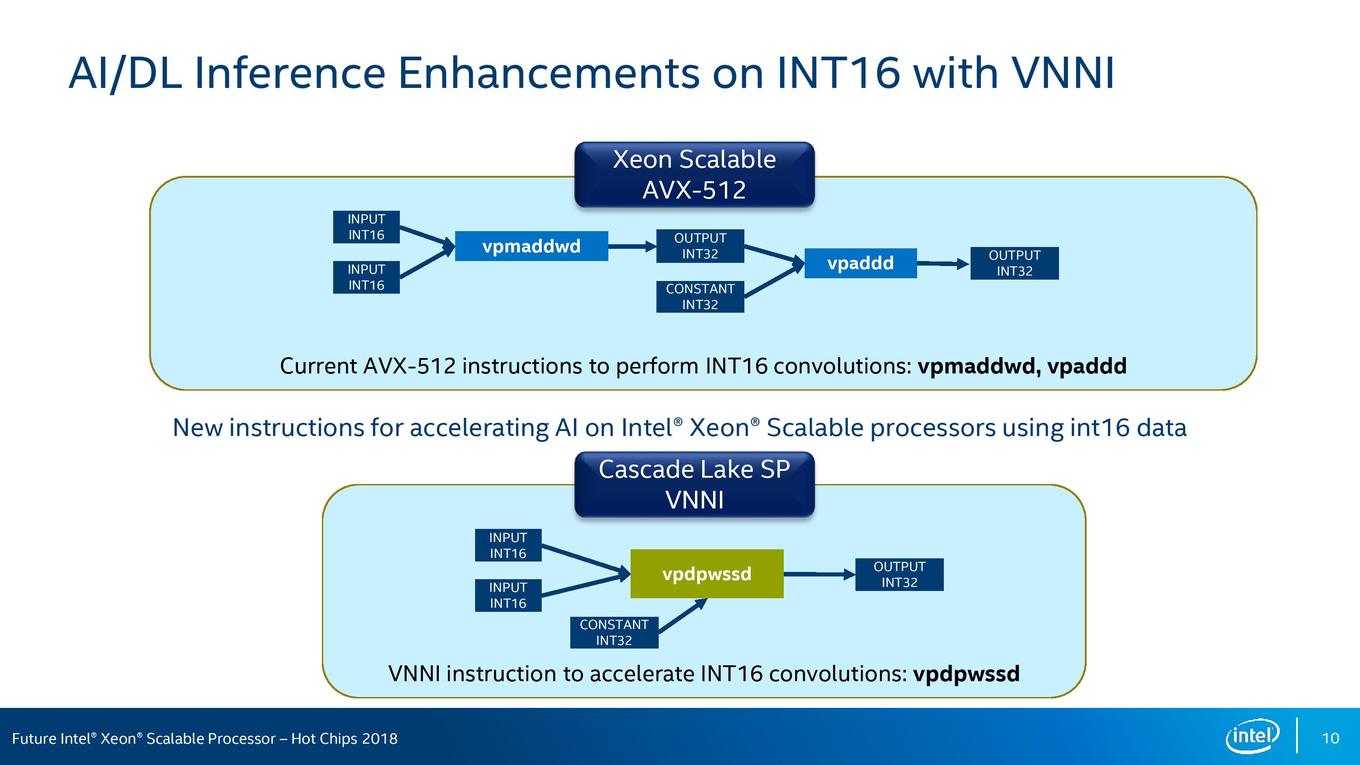

As well as the additional operations, SIMD (single instruction, multiple data) is a thing to be reckoned with. Primarily, it was used to perform simple operations (such as an addition) on “vectors” of data. In this case, “vectors” meant loading the data from the memory to the wide registers of the CPU, processing it with a single instruction and then repeating. Nowadays, AVX-512 allows both long registers (512-bit wide) as well as the sophisticated operations, which are useful for neural network tasks for both inference and training.

If you’re running some scientific/research code on your local powerful computer, this is a place to stop reading, just build your code with -march=native (/arch on MSVC) switch and enjoy all the benefits your hardware can provide. However, if you’re planning on distributing your software, there might be a little problem. By default, modern compilers don’t utilize any of the vector extensions to make the resulting program as portable as possible. This is a good approach, but owners of the modern hardware won’t be as happy, as they could’ve been. Today I’d like to discuss and implement a dispatcher pattern, which is used in the Intel IPP library.

The main idea is to put the most performance-critical code into a separate library, build several variants of it and dispatch the calls at the runtime. In this post, I’ll only consider shared (dynamic) libraries, since it’s easier to implement, but with several tweaks, you may get a static executable with the same functionality

Benchmarking first

As in any optimization related article, first of all, one must benchmark various aspects and parts of an application and decide, which functions should be extracted for the library. My toy example happened to have such a function:

extern "C" void Add(const double* a, const double* b, std::size_t length, double* dst) {

for (int i = 0; i < length; ++i)

dst[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

Yup, I know, raw pointers, but you don’t want to pass C++ objects in and out from the dynamic library, trust me.

So I’ve measured this code on my machine with a Google Benchmark and got these result for 256 elements:

| Instruction set | Time, ns |

|---|---|

| Common | 95 |

| AVX | 40 |

| AVX2 | 30 |

I’d like to point out that I haven’t hand-optimized any of the code, haven’t used any intrinsic functions or whatever, just recompiled with the change of one flag: /arch. Triple performance is a target worth pursuing, so this is a perfect candidate for such an optimization, so let’s proceed to the next step.

Creating a library

As we’ve decided with the functions we’ll be extracting, the next step is to create a library. This is as straightforward as it gets: a pair of header and a source file:

#pragma once

#include <cstddef>

#include <cstdint>

namespace lib {

extern "C" void Add(const double * a, const double * b, std::size_t length, double * dst);

}

#include "lib.hpp"

extern "C" void lib::Add(const double* a, const double* b, std::size_t length, double* dst) {

for (int i = 0; i < length; ++i)

dst[i] = a[i] + b[i];

}

And we’ll use the basic CMake script to generate a library:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.10)

project(best_instruction_set)

set(SOURCES src/lib.cpp)

set(HEADERS

src/lib.hpp

src/lib.def

)

add_library(best_instruction_set SHARED ${SOURCES} ${HEADERS})

set_property(TARGET best_instruction_set PROPERTY CXX_STANDARD 17)

set_property(TARGET best_instruction_set PROPERTY CXX_STANDARD_REQUIRED ON)

Delayed library loading

The key to the dispatcher is the delayed loading of the library. This is a concept when the library is being loaded in some moment at runtime and a developer assigns function pointers to the exported functions of a library.

For this purpose I’ve written a simple cross-platform wrapper, which is used as-is for multiple projects:

#pragma once

#include <stdexcept>

#include <string>

#ifdef _WIN32

#include <Windows.h>

#else

#include <dlfcn.h>

#endif

namespace DllWrapper {

#ifdef _WIN32

using InstanceType = HMODULE;

#else

using InstanceType = void*;

#endif

inline auto GetInstance(const char* path) {

#ifdef _WIN32

return LoadLibraryExA(path, nullptr, 0);

#else

return dlopen(path, RTLD_LAZY);

#endif

}

inline void FreeInstance(InstanceType instance) {

if (!instance)

return;

#ifdef _WIN32

FreeLibrary(instance);

#else

dlclose(instance);

#endif

}

inline auto GetAddress(InstanceType instance, const char* symbol_name) {

#ifdef _WIN32

return GetProcAddress(instance, symbol_name);

#else

return dlsym(instance, symbol_name);

#endif

}

}

Based on this common wrapper, every library has to get a custom wrapper, such as the following:

#pragma once

#include "lib.hpp"

#include "wrapper_common.hpp"

#include "cpuinfo_x86.h"

#include <string>

#include <string_view>

struct LibWrapper {

void (*Add)(const double* a, const double* b, std::size_t length, double* dst) = nullptr;

LibWrapper() {

auto path = std::string("best_instruction_set");

#ifdef _WIN32

path += ".dll";

#elif __linux__

path = "lib" + path + ".so";

#else

throw std::runtime_error("Unexpected system");

#endif

instance = DllWrapper::GetInstance(path.c_str());

if (!instance)

throw std::runtime_error("Unable to load library " + std::string(path));

Assign("Add", Add);

}

~LibWrapper() {

DllWrapper::FreeInstance(instance);

}

private:

DllWrapper::InstanceType instance = nullptr;

template <typename T>

void Assign(const char* symbol_name, T& dst_pointer) {

auto address = DllWrapper::GetAddress(instance, symbol_name);

if (!address)

throw std::runtime_error("Unable to find symbol: " + std::string(symbol_name));

dst_pointer = reinterpret_cast<T>(address);

}

};

This wrapper is a class with a function pointer and a bare-bones logic. In the constructor, the library is loaded and the pointer is assigned via the helper function. In the destructor, the binary resources are released.

Generating multiple libraries

There’s a simple extension to the provided CMake script, which will allow us to generate multiple libraries from the same source code at the same time:

set(ARCHITECTURE_OPTIONS "avx;avx2;avx512")

foreach (INSTRUCTION_SET ${ARCHITECTURE_OPTIONS})

message(STATUS "Generating ${INSTRUCTION_SET} library")

add_library(best_instruction_set_${INSTRUCTION_SET} SHARED ${SOURCES} ${HEADERS})

if (WIN32)

string(TOUPPER ${INSTRUCTION_SET} UPPERCASE_INSTRUCTION_SET)

set(COMPILER_OPTION /arch:${UPPERCASE_INSTRUCTION_SET})

elseif (UNIX)

set(COMPILER_OPTION -m${INSTRUCTION_SET})

if (${INSTRUCTION_SET} STREQUAL "avx512")

set(COMPILER_OPTION -m${INSTRUCTION_SET}f)

endif (${INSTRUCTION_SET} STREQUAL "avx512")

endif(WIN32)

target_compile_options(best_instruction_set_${INSTRUCTION_SET}

PRIVATE ${COMPILER_OPTION}

)

set_property(TARGET best_instruction_set_${INSTRUCTION_SET} PROPERTY CXX_STANDARD 17)

set_property(TARGET best_instruction_set_${INSTRUCTION_SET} PROPERTY CXX_STANDARD_REQUIRED ON)

endforeach(INSTRUCTION_SET)

Detecting the processor architecture at runtime

For this, we’ll be using one of the Google side-projects, cpu_features. It will extend the library wrapper class in such a manner:

static auto GetSuffix() -> std::string {

const auto features = cpu_features::GetX86Info().features;

if (features.avx512f)

return "avx512";

else if (features.avx2)

return "avx2";

else if (features.avx)

return "avx";

return "";

}

Since we’re using suffixes to distinguish our libraries, this is good enough. So the constructor of the wrapper will be extended as well:

LibWrapper() {

SwitchImplementation(GetSuffix());

}

void SwitchImplementation(std::string suffix) {

DllWrapper::FreeInstance(instance);

auto path = std::string("best_instruction_set") + (suffix.empty() ? "" : ("_" + suffix));

#ifdef _WIN32

path += ".dll";

#elif __linux__

path = "lib" + path + ".so";

#else

throw std::runtime_error("Unexpected system");

#endif

instance = DllWrapper::GetInstance(path.c_str());

if (!instance)

throw std::runtime_error("Unable to load library " + std::string(path));

Assign("Add", Add);

}

Using the library

And that’s pretty much it. One last this is to use the library, which we’ll be doing through the wrapper we’ve just created:

#include "lib_wrapper.hpp"

#include <iostream>

#include <vector>

int main() {

try {

std::vector<double> a(64, 1);

std::vector<double> b(64, 2);

std::vector<double> dst(64);

auto wrapper = LibWrapper();

wrapper.Add(&a[0], &b[0], a.size(), &dst[0]);

// wrapper.SwitchImplementation("avx512");

// wrapper.Add(&a[0], &b[0], a.size(), &dst[0]);

}

catch (const std::exception& e) {

std::cerr << e.what() << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}

This is a basic example, but you’re free to play with it in the repository. Looking forward to all the feedback and discussions about this approach and have a nice day.